Welcome and Introduction

Welcome to this special issue Eurogas newsletter, which focuses on Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) and its importance to delivering the energy transition. We are extremely grateful to the contributors for spending the time to pen their thoughts on these topics.

This issue brings you a co-authored article by the Chairman and CEO of Sempra Energy Mr Jeffrey Martin and Former United States National Security Advisor Mr H. R. McMaster, who discuss the important role US LNG can play in supporting the European energy transition as we emerge from the pandemic.

We are delighted to say that MEP Jerzy Buzek, the Former Prime Minister of Poland and Former President of the European Parliament has also contributed an article. In his piece he recounts the pivotal role developing US and EU LNG has had on delivering energy security for the EU.

We are also honoured to have experts from the Oxford Institute of Energy Studies, Mr David Ledesma, Chairman of the Natural Gas Programme and Senior Research Fellow Mr Mike Fulwood, who examine and explain the importance of LNG imports for the European Union’s energy transition.

In Eurogas, we recognise the role that LNG plays in enabling the continued reduction in carbon emissions in the EU, as more Member States switch to gas from coal and oil. This also facilitates a reduction in detrimental air pollutants, while offering market diversification for affordable energy. LNG plays a key role in supporting the European Union to have an effective, efficient gas market that is one of the most liquid energy markets in the world.

Europe is increasing the quantity of LNG it imports, including from the US, and is building the accompanying infrastructure that is needed to deliver its benefits. This is an infrastructure that we will use going forward, as we reach our ambition for net zero emissions in 2050, as in time it will also deliver hydrogen from around the world. LNG and its infrastructure will play a vital role in Europe’s energy transition.

We hope you enjoy this special edition and once again my sincere thanks to the renowned authors for their contributions.

Stay well,

James

Global Challenges Require Multinational Solutions

More than a year after a pandemic brought global economies to a halt, many communities around the world are still reeling. Today, we are facing two formidable challenges: a post-COVID recovery and a climate crisis. Both require international cooperation and the acceleration to cleaner, affordable and reliable energy systems. With the United States re-joining the Paris Agreement, expanding cooperation between the U.S. and Europe holds renewed promise for greater alignment with other regions of the world as well as critical new innovations in the production, transportation and consumption of energy.

But the Paris Agreement is just the start. Addressing the interconnected global challenges of reducing emissions, ensuring access to clean energy, and improving food and water security will require a collaborative, systemic and holistic approach. Addressing one challenge at a time can exacerbate others and perpetuate rather than prevent the dangers of climate change. The priority action that has broad political and commercial appeal not only in prosperous nations, but also in developing economies, is to produce more energy for more people with lower carbon content.

The development of cleaner and affordable energy overcomes one of the most fundamental flaws with climate proposals: single-country solutions. The International Energy Agency (IEA) concluded in its 2021 World Energy Outlook that unilateral approaches will not work. “In the absence of greater international cooperation, it will take several decades longer to reach net-zero emissions globally,” said IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol. Indeed, in the absence of commercially viable solutions to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, China, India and other developing economies experienced a 1.5 percent increase in emissions per year in the four years following the signing of the Paris Agreement.

There is another path forward. The U.S., which has long recognized that energy security is vital to national security, offers a case study on how to lower carbon emissions while fuelling economic growth. The IEA’s 2020 World Energy Outlook noted that the U.S. led the world in the largest reduction of man-made GHG emissions over the last 20 years (down almost 1 gigaton from a 2000 peak). Expanding investments in renewable power generation while using abundant natural gas (with its lower emissions footprint) precipitated a dramatic decline in coal’s share of U.S. electricity generation. In just 12 years, coal-fired power generation went from providing nearly half of America’s energy to less than 22 percent. Even more remarkable is that these reductions took place at the same time as significant economic expansion and rising energy demand. By diversifying its energy supply to include lower- and zero-carbon fuels, the U.S. was able to ramp up electricity generation to support a doubling of its GDP while effectively lowering man-made emissions. Other countries can replicate that success. The impact of displacing coal was made even more clear in the recent Group of Seven (G7) call to halt all government support for the use of coal in power production.

The European Union’s (EU) commitment to energy diversification has yielded similar achievements. As the biggest importer of natural gas in the world, the EU has been a leader in the development of liquefied natural gas (LNG), its associated infrastructure and the creation of liquid and transparent natural gas markets. A recent S&P Global Platts story noted how Europe is steadily cementing a key leadership role in the global LNG trade. “Today, when talking about the future of European gas supply, LNG is firmly viewed as a core part of the supply stack; critical to meeting long-term demand,” the article said. No longer dependent on a few dominant suppliers, diversification of the EU’s natural gas supplies and a notable uptick in U.S. LNG imports has also supported market competitiveness and set the stage for maximizing further renewable penetration.

Over the next two decades, the greatest challenge lies outside the U.S. and EU. The IEA projects that emerging and developing economies, including China, will account for 90 percent of the growth in global GHG emissions. This projection highlights why access to affordable and diverse energy supplies is essential to reduce carbon emissions while supporting stable and prosperous economies. The growth of affordable renewable energy in these markets will help but, ultimately only meet about 28 percent of the world’s total energy demand by 2050.

Moreover, for countries with waning natural gas production, LNG offers an important way to continue expanding renewable energy. The U.S. and EU are poised to achieve quick wins for the climate by displacing coal and oil with natural gas not just in power grids, but also in manufacturing and other hard-to-decarbonize sectors. Smart, new infrastructure investments that enable these GHG reductions today will also propel tomorrow’s energy technologies. On the horizon is a hydrogen economy that can be powered with cleaner molecules as emerging technologies come online.

This is the decisive decade for tackling climate change, and we are optimistic. Just as the rapid development of vaccines was foundational to overcoming the global pandemic, clean and adoptable energy solutions are essential to attacking the threat from climate change, while also overcoming other interconnected challenges to global security and prosperity. In conclusion, it is not a Hobson’s choice between economic growth and sustainable initiatives to mitigate climate change. Leadership and international cooperation with the right priorities can advance energy security, economic prosperity and environmental progress.

Mr Jeffrey W. Martin, Chairman of the Board and CEO of Sempra Energy.

Mr H. R. McMaster, Former U.S. National Security Advisor, Retired Lieutenant General of the Army of the United States of America.

Gas for Transition and Security in the European Union

Relief, joy and satisfaction: that is what arrived for me on 8 June 2017 into the Polish terminal of Świnoujście. These sentiments were accompanied by an American shipment of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG.)

It wasn’t the first shipment to arrive in Europe; that was a year earlier into Portugal. But it was the first for Poland. I took a lot of pride in that, because liberalisation of rules on the US oil and gas exports was one of my core priorities as the European Parliament Chairman of the Committee of Industry, Research and Energy (ITRE).

In 2015 on my initiative, we launched high-level Transatlantic political and business talks on LNG partnership in the framework of the EU-US LNG Roundtables. And now, this long-awaited and much-needed win-win was becoming a reality. A win for our energy security, industry and cooperation with America.

Indeed, diversification of European energy supplies – both in terms of sources and routes – was a main objective of our Energy Union proposed on 25 February 2015. We took many firm and deliberate actions to improve and strengthen European Union’s energy security and resilience; the development of an LNG strategy and LNG imports are some of the results. Even if unfortunately there are still challenges with some gas infrastructure projects to be addressed in the EU, energy supply is incomparably more secure today. Let us admit it, but we should never take it for granted.

Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic we saw dynamic growth for LNG. By the end of 2019, LNG imports into the EU from the US had reached a record 3.2 billion cubic meters. So as well as diversification, LNG has resulted in more competition to the EU energy market, bringing with it lower prices for both industrial and individual consumers.

Today, while implementing the European Green Deal, let us always remember: clean energy transition towards EU’s climate neutrality in 2050 is essential, but it must not be at the cost of energy security. EU measures to deliver lower carbon natural gas and cleaner gaseous fuels such as hydrogen must in tandem help ensure an important role for gas in the transition, which in turn reinforces energy security.

We did not tighten the security of natural gas supply yesterday to disregard this issue in the context of hydrogen supply today and tomorrow. The same principles apply equally to renewable and decarbonised gases. In addition, we need greater acknowledgment that for some Member States the path to decarbonisation will require a short-term increase in the consumption of natural gas.

Poland is one example, which is planning to install an LNG floating storage and regasification unit (FSRU) in the Bay of Gdańsk by 2024-25 to meet growing gas demand, particularly in heating and power generation. This is in addition to the expansion of the LNG terminal in Świnoujście from 5 bcm per year to 7.5 bcm, which includes construction of a second jetty for loading and unloading LNG carriers.

We see this flexible fuel as an essential contributor that will allow Poland to facilitate phasing-out of solid fossil fuels, support the transition to a sustainable energy future, and continue to safeguard Polish energy security. And if all those objectives are met, this would be another great reason for relief, joy and satisfaction.

MEP Jerzy Buzek, Member of the European Parliament, President of the European Parliament, Prime Minister of Poland.

The Importance of the EU’s LNG Market in a Global Context

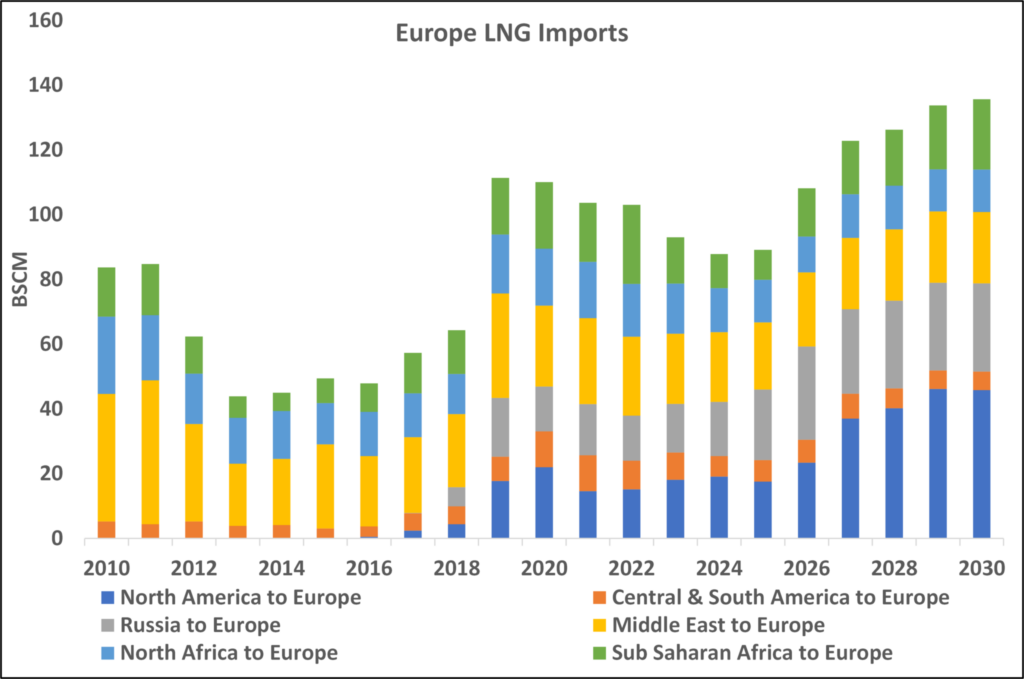

In the last couple of years LNG has become an increasingly important source of gas for Europe, [1] as an alternative to pipeline gas, so underpinning diversity of supply and widening the choice of different supplier countries. In 2010 LNG represented 14 per cent of Europe’s gas supply (pipeline imports 33 per cent), falling to 10 per cent in 2015 (pipeline imports 39 per cent) but by 2020 this had increased to 20 per cent (pipeline imports remaining at 39 per cent), as indigenous production, especially from the Netherlands, declined.

After declining in early 2010s as European gas demand fell sharply, LNG imports began to recover, initially as European demand recovered, and then rose sharply in 2019 as more LNG supply came on to the market and Europe, with its abundant storage was able to absorb the rising supply. As shown in Figure 2, the surge in supply came almost totally from North America (the US) and Russia (Novatek’s Yamal LNG project). New sources of supply from the US means that more LNG is readily available to the European market from Atlantic Basin sources. However, as LNG is traded on a global market with flexibility of supply, it is available to any market when their demand increases. This may ‘pull’ LNG cargoes away from European markets to those offering higher prices, with the European market replacing the ‘lost’ supply through increasing pipeline imports or, initially, taking additional gas from storage. This was seen most acutely in December 2020/January 2021 where extreme cold weather in Asia, coupled with LNG supply cutbacks from some LNG supply sources, drove Asian prices to high levels. Gas prices in Europe at that time rose marginally, but not to the levels experienced in Asia, so LNG cargoes destined for Europe were diverted to the higher value Asian market. Europe ran down gas in storage to offset the decline in LNG imports. Effectively European gas storage was used to supply Asia’s higher gas demand, reversing the large storage injection in 2019. By its nature the European gas market, with 78 per cent of gas consumption based on Gas on Gas (hub) pricing, [2] is flexible enough to manage its sources of gas and LNG through price. Increasingly the LNG market is becoming global with close interlinkages between Europe and the key demand Asian region with the destination of marginal cargoes being determined by the regional ‘spot’ price. LNG imports into Europe therefore reflect changing global demand patterns and periods of supply surplus and tightness.

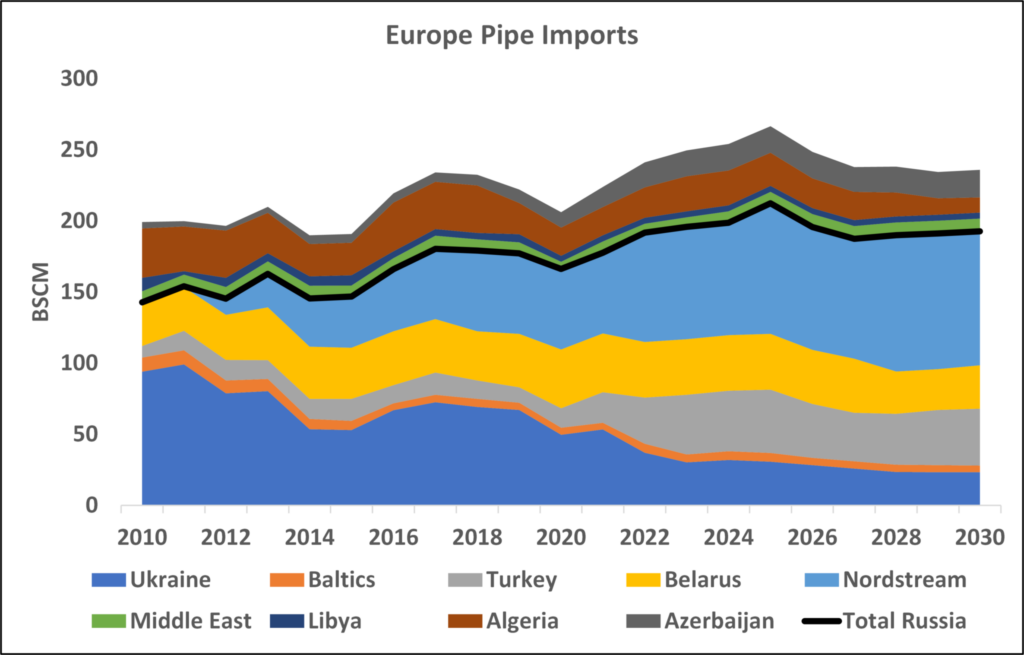

The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (OIES) has modelled [3] European gas/supply to 2030 and the future trend for European pipe and LNG imports. This, together with historical numbers back to 2010, are set out in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1: European Pipe Imports 2010 – 2030. (Source: OIES, IEA and Nexant World Gas Model)

Figure 2: Europe LNG Imports 2010 – 2030 (Source: OIES, IEA and Nexant World Gas Model)

OIES’s analysis shows that European pipe imports (Figure 1) are expected to recover from the low 2020 levels, through to the mid-2020s, as volumes from Azerbaijan increase as well as the delayed Nordstream 2 beginning operations. As the next wave of LNG supply comes onto the market, however, pipeline imports ease back a little. Europe saw an increase in LNG imports in 2019/20 to over 110 Bscm. The current surge of European LNG imports is expected to fall as global LNG demand rises without a corresponding increase in new LNG supply. In 2021 this may lead to a marginal tightness in the market as strong European storage injection is expected to happen without a corresponding increase in LNG imports. The interesting period to examine is the years between 2022 and 2026. During this period, the LNG market is expecting a reduced volume of new LNG supply to arrive onto the market. The surge in final investment decisions (FIDs) was in 2019 and most of these are not expected to come online until 2024/5 [4]. There are, therefore, only a few projects scheduled to start up over the next three years. This period of tighter supply means that some Middle East LNG is likely to be diverted to Asian markets with reduced LNG import volumes into Europe during this period. This next wave of supply is expected to lead to another surge in European LNG imports to well above the historically high 2019/20 levels, reaching over 130 Bscm by 2030.

Future demand for gas as a fuel is, however, uncertain as Europe seeks to reduce emissions and move to cleaner energy sources as it moves towards its pledge of net zero emissions by 2050. The question is – what will be the role of gas in this transition? For the period up to 2030 therefore, gas demand in Europe is, according to OIES modelling, expected to be similar to that expected in 2030 at around 550 Bcm (with a dip in 2021/21 due to lower economic activity due to the pandemic).

LNG has been, and will increasingly become, a key source of gas to the European market. As part of a global supply system, LNG will be priced more and more on fundamental supply/demand factors with the regional markets attracting cargoes based on price. LNG will be a reliable source of gas to Europe, though at times some cargoes will be diverted to other higher value markets especially during periods of high prices and when Asian buyers seek to secure additional spot price related LNG cargoes. At other times, Europe will be a place to ‘store’ excess LNG supply. The European market though is flexible enough to perform this balancing role by using its storage facilities and gas pipeline imports, reflecting Europe’s gas supply demand flexibility and its overall place in the global gas market.

Europe is defined as the EU27, Norway, UK, Switzerland, Serbia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, North Macedonia and Turkey

IGU, Wholesale Gas Price Survey 2020 Edition

Modelling uses the Nexant World Gas Model, IEA data and OIES estimates.

An LNG project usually takes ~ 5 years to reach plateau exports following an LNG FID

Mr David Ledesma, Chairman Natural Gas Programme, Oxford Institute of Energy Studies.

Mr Mike Fulwood, Senior Research Fellow, Oxford Institute of Energy Studies

Eurogas Spotlight On Newsletters

We hope you enjoyed this special issue Eurogas newsletter. For more of our work on the energy transition, as well as press releases, policy papers and upcoming events, please go to Home : Eurogas

If you would like to host a newsletter please contact the team at: eurogas@eurogas.org